Hello WRF Community,

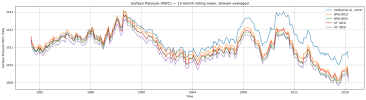

I observed a time shift in wind speed and direction while running a 25-year climate simulation (1991–2016) using NDOWN downscaling from a 21-km parent simulation to a double-nest, 2-way simulation with resolutions of 7 km (d01) and 2.3 km (d02).

During my test runs (3-year runs starting September 2013) with multiple configurations, I did not observe such shifts. In those tests, wind direction and magnitude were coherent with observations. It seems that the shifts appear only over very long simulations.

For my long-term simulation, I used the initial wrfinput* file generated by NDOWN, starting 1991-02. I am now a bit desperate because these are very long and computationally intensive runs. Initially, I regularly checked my outputs for the first decade, and as all seemed normal, I let the runs continue.

I am unsure what could have caused this. Should I have used monthly NDOWN-generated wrfinput files to re-initialize the runs correctly? This seems contradictory to the idea of letting the simulation run after spin-up.

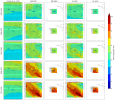

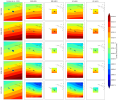

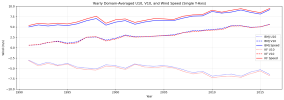

I have attached a couple of figures for d02 (90x90 grid cells, 2.3-km resolution, centered on Tahiti, 17.5°S, 149.5°W) :

Thank you in advance!

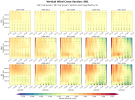

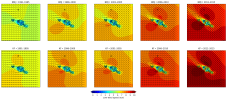

2025/12/06: I added the domains dimensions as a figure for a better understanding.

I observed a time shift in wind speed and direction while running a 25-year climate simulation (1991–2016) using NDOWN downscaling from a 21-km parent simulation to a double-nest, 2-way simulation with resolutions of 7 km (d01) and 2.3 km (d02).

During my test runs (3-year runs starting September 2013) with multiple configurations, I did not observe such shifts. In those tests, wind direction and magnitude were coherent with observations. It seems that the shifts appear only over very long simulations.

For my long-term simulation, I used the initial wrfinput* file generated by NDOWN, starting 1991-02. I am now a bit desperate because these are very long and computationally intensive runs. Initially, I regularly checked my outputs for the first decade, and as all seemed normal, I let the runs continue.

I am unsure what could have caused this. Should I have used monthly NDOWN-generated wrfinput files to re-initialize the runs correctly? This seems contradictory to the idea of letting the simulation run after spin-up.

I have attached a couple of figures for d02 (90x90 grid cells, 2.3-km resolution, centered on Tahiti, 17.5°S, 149.5°W) :

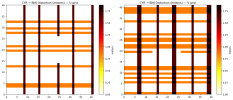

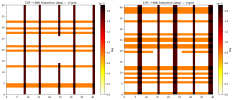

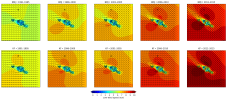

- Average maps of wind speed/vectors over 5 windows of 5 years each.

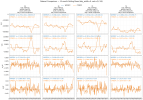

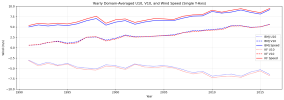

- Yearly domain-average U10MEAN, V10MEAN and SPDUV10MEAN plots showing the observed shift.

Thank you in advance!

2025/12/06: I added the domains dimensions as a figure for a better understanding.

Last edited: